Astronomy Column | La Silla Observatory: A Place Where Moments Are Immortalized

Posteado

Cielos Chile

schedule Wednesday 25 de October

Column originally published in Emol.com

In the mid-20th century, representatives of institutions in Europe and North America visited the regions of Atacama and Coquimbo to find the ideal place to install astronomical observatories in the southern hemisphere. They were looking for a place to settle to observe what was elusive from latitudes north of the equator, such as parts of the center of the Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds. The geographical, climatic, and political characteristics of the country had been publicized by national scientists of the time: Chile offered an extremely dry desert, where there were hills with heights over 2200 meters above sea level and auspicious weather patterns for astronomy, good infrastructure, and support from the State.

The European Southern Observatory (ESO) signed an agreement with the State of Chile 60 years ago for the construction and installation of the La Silla Observatory on the hill formerly known as Cinchado. This agreement describes arrangements regarding the construction, staffing, and installation of the observatory, the delivery of studies by Chile on the territory, and facilities granted such as tax exemptions, recognition of the institution’s international personality, and immunities for its members. The ESO 1-meter photometric telescope was the first to take images of star clusters and the Magellanic Clouds from La Silla in 1966. Two years later, two telescopes with twins in France made their first observations: the Grand Prisme Objectif capable of obtaining spectra of multiple objects at the same time, and the ESO 1.52-meter specially designed for stellar spectroscopy and astrophotography.

However, they were not the first eyes to observe from La Silla nor the ones that generated images of what they saw.

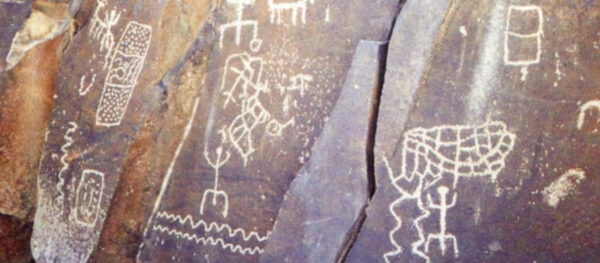

Descending the northeast side of where the ESO 3.6-meter telescope is located, there is the Los Tambos ravine, and in it, a few hundred blocks of granite and andesite with engravings. The archaeologist Hans Niemeyer and the astronomer Dominique Ballereau tell us about this rock art in a 1996 article, where they classify the different petroglyphs into two categories: biomorphs and abstract geometric signs. The possible creators of the engravings may have belonged to the El Molle Cultural Complex, a pre-Columbian people that developed in part of the Norte Chico between 300 B.C. and 700 A.D. The geometric signs are distinguished as circles, spirals, lattices, and frets, sometimes grouped in completely abstract engravings that occupy almost the entire surface of the block, images that are perhaps the result of practices with psychotropic substances. Among the biomorphic engravings, even for untrained eyes, it is easy to distinguish anthropomorphic figures and camelids.

My favorite panel shows an interaction between biomorphs: two human figures with camelids of different sizes in rows under a small concentric circle from which multiple rays emerge that pass through an outer circle, which in my view would represent the sun. Next to that figure, there is another circle from which rays also emerge that end in an outer circle, which for me is the moon. I have gone several times to La Silla to observe with the NTT telescope and the 3.6-m, and one of my favorite things during the day, apart from the ice cream machine, is to look for the animals found at the observatory. Currently, donkeys and vizcachas are quite common, and I have been lucky enough to see solitary guanacos among the domes or in groups moving from one side to the other of the road to the observatory, just as they are shown on the panel.

It is not possible to know if what the engraved panels show happened at La Silla or what those who made them really wanted to communicate, but they undoubtedly chose that place, more than 1900 meters above sea level, to immortalize a moment, the same as the cameras of the observatory’s telescopes did and do, initially on photographic plates and now in CCD images. La Silla is then a place where the past is immortalized, where moments in time can be appreciated, whether in rock art or in the observation of the universe, which will always be an image of the past whether of a star, a cluster, or a galaxy, due to the constant speed at which light travels. It is a place where two disciplines that study the past, astronomy and archaeology, meet. On June 27 of this year, the decree identifying La Silla among the areas with scientific and research value for astronomical observation was published in the official gazette of Chile. And just as the dark skies in that area must be protected, a new Heritage Law is undoubtedly necessary to protect the rock art of the sector as archaeological heritage from a broad perspective, not only from the historical-artistic one, updating the 1970 law.

Author: Bárbara Rojas-Ayala

She holds a Ph.D. in Astrophysics from Cornell University (United States). She currently serves as an academic at the Institute of Advanced Research (IAI) – University of Tarapacá and a researcher at the Center of Excellence in Astrophysics and Associated Technologies CATA.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive relevant information about the skies of Chile every month